MAKING A LAYERED-BLANK ROCKET

Introduction

This is the simplest type of rocket to create because all the laminations are along the length of the blank.

Woodworking is an inherently dangerous activity. The non-woodworking techniques described here aren't all that safe, either. Sharp tools, powerful motors, big lumps of wood, chemicals, fumes, etc. can cause you serious bodily injury or even death. These pages are NOT meant as a substitute for instruction by a qualified teacher, just as an illustration of how I do certain things. I take no responsibility for any mishaps you may experience during a fit of inspiration. You've been warned.

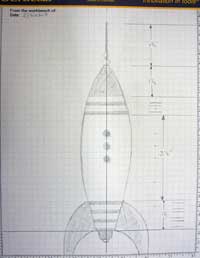

Photo 1

The whole process starts with a design. I prefer graph paper to plain to work out the proportion and dimensions. Then I choose wood species appropriate to the design. The design may change as the rocket is built, but it’s still essential to have something to start from.

In this case, I made two rockets at the same time and chose maple (light sections) and bubinga (dark sections) for one and maple and padauk for the other.

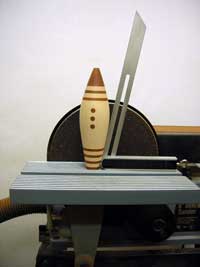

Photo 2

The components of the body are cut and glued up. In this case, I used a large maple dowel for the body and slices of square padauk and bubinga for the stripes, nose and base. In order to keep everything lined up properly, I drilled holes through the center of each section and used small dowels to aid in keeping the sections straight and aligned.

Photo 3

The rocket body blank mounted on the lathe and ready to be shaped.

Photo 4

When the rocket is near its final shape, I drill the 3/8” hole for the portholes.

I drilled a small pilot hole and then use a 3/8” forstner bit in a hand-held power drill. The pilot hole helps to guide the point of the forstner bit at the start of the hole, so it doesn’t walk around too much and chew up the rocket surface. Reducing tearout on the hole’s edge means less clean up afterwards.

Photo 5

Since dowels are not readily available in either bubinga or padauk, I turn my own to make the portholes.

If you look closely, you can see that I took a bit of square stock in the chuck and turned it to a cylinder, then tapered the end of the cylinder. The taper helps me to size the dowel properly to the hole. After sizing the dowel for one porthole, I cut off what I need, make another taper and do the next porthole.

Photo 6

Here’s the rocket with the three portholes in place, finish turned to its final shape and sanded. I sand through progressive grits, ending up at P800.

Photo 7

I needed a template for the fins. Scrap thin plywood and pencil sketches are the way to go. Cardboard works, too, I just never have any around.

Photo 8

The bottom of the fins will have a slight angle because of the taper of the rocket. I use an angle guide to measure the angle….

Photo 9

....and transfer it to the fin blanks after cutting the fins to shape on the bandsaw and sanding the edges smooth.

Photo 10

Once the fins have been fitted to the rocket body, I glue them up. The scrap wood underneath the rocket body supports it until the glue sets.

To get the slight curvature in the fin where it joins the rocket body, I use different size dowels wrapped with 100 or 120 grit sandpaper. The fit doesn’t need to be perfect, but it needs to be close so the glue will hold properly.

Photo 11

The completed rocket. I usually use satin polyurethane gel varnish or satin spray lacquer for the finish. With either finish, I apply three coats and buff lightly in between with ultra-fine synthetic steel wool.

Rocket from “A Supply Ship Arrives” (2007)